Dystopia Deferred

On Fernando Flores' new novel of fascism and volcanic winter, Brother Brontë

Given the sense of fatalism that has come to pervade American life — self-mutilating politics, a downwardly mobile economy, stagnating cultural production, different ecologies collapsing by the day — it’s prime time to indulge in some apocalyptic thinking. Brother Brontë, the new novel by Fernando Flores, fits the brief admirably, conjuring as it does a world where the most toxic components of our contemporary reality have been extended to their logical conclusion.

The setting is Three Rivers, a small town in South Texas that was transformed into a city by tech money overnight, before all the half-finished buildings were abruptly abandoned as the attention of the responsible oligarchs veered elsewhere. (Take heed, ye residents of the freshly incorporated Starbase, TX!) There has been a major crackdown on immigrant communities, leading to an exodus of Hispanics back to their ancestral homes in Latin America. Books are somewhere between heavily regulated and outright illegal, with roving gangs of fascist teens destroying each confiscated title with a baroque machine whose “micro-blades pulverized the book entirely, dust blowing into the wind after the procedure like a wildflower bouquet’s ashes.” Women have been pushed into subservience, their only opportunity to make something like a living coming via indentured servitude at the Big Tex Fish Cannery.

How much of this is the work of Three Rivers’ dictatorial mayor versus emblematic of national or global upheaval is left unsaid. Indeed, the world beyond Three Rivers remains fuzzy. There’s a stray mention to Senate hearings about the “New Way Forward,” a suggestion that Texas is operating under its own sovereignty. The only missives from the outside world that arrive in the city come by way of “newscubes” that play a prerecorded report, whoever produces the program never even bothering to update the prevailing air temperature between the morning and afternoon weather broadcast.

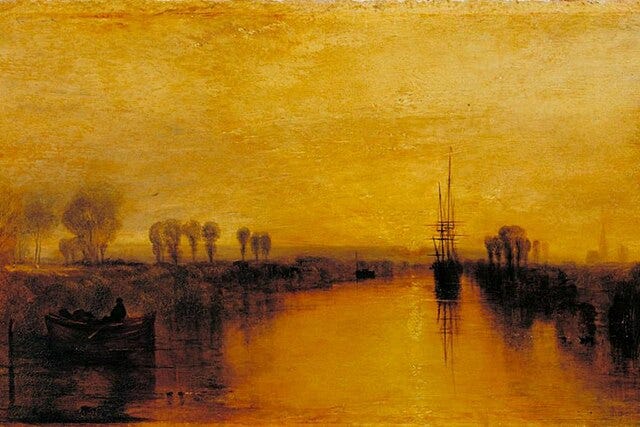

All of this makes Three Rivers a black box, with the blackness made literal midway through the novel by the smoke of a volcano exploding in Mexico that billows north, obscuring the sky for months on end. “With the absence of regular sunshine,” Flores writes, “the color spectrum tended to carry the limited range of a rare monochromatic rose. One had to shine a lamp a few feet away from a subject to make out elusive greens, or oranges, fuchsia, or even a stark white. Automobile headlights from drivers braving the haze often revealed patches of layered street graffiti and the fact that Three Rivers’ street signs had originally been navy blue.” On a walk through this murky city, one of Flores’ protagonists lifts a lantern in search of a statue known as Brown Apollo that ought to be nearby, but “the halogen couldn’t pierce the low-flying ash and smog clusters between them, so she continued on her way.”

Despite the dire situation in Three Rivers, Brother Brontë is punctuated with moments when the outside world does break through, making clear that the city’s dystopia is hardly the only future available to us. One of the many motifs Flores swipes from the Victorian tradition referenced by his title is the novel-within-a-novel, which in this case offers clues about the global situation by way of the story of how a writer named Jazzmin Monelle Rivas came to compose her own book titled Brother Brontë “in a contrived style she later confessed felt like it never belonged to her” (after all, her other books are quasi sci-fi works with names like I Was a Teenage Brain Parasite and Ghosts in the Zapotec Sphericals).

After Rivas boards a ship in New Orleans bound for an unnamed port in Latin America, she discovers most of the women aboard “were refugees escaping domestic abuse and the new laws back home. Though all the women were citizens, they’d been forced to leave the country.” Once disembarked, Rivas is enchanted with a nation quite unlike the one she left, even if it, too, faces political instability. As she watches fireworks made from confiscated munitions explode in the sky, a local explains, “The Rentists are fighting a revolution without weapons. Did you know that? It’s the only revolution of its kind, that’s why it really feels like things are happening, that things are finally real.”

Again, Flores is scant on details, allowing a sensation of possibility to serve as its own destination. And that sensation is not limited to foreign shores. Once the book returns to its volcanic present, a young woman named Moira goes searching for her long lost twin sister (eat your heart out, Charles Dickens) in the rural community of George West, just ten miles down I-35 from Three Rivers. There, she learns

in George West, the people were against the privatization of their city, and had done away with their mayor, commissioners, and police in an orderly upheaval. A rotating committee of diverse citizens voted annually to distribute resources and land throughout the community, and any disputes were settled democratically.

George West is hardly a one-size-fits-all utopia — indeed, Moira herself finds the ag life dull and longs for the congestion and chaos of Three Rivers. But it at least exists as a world apart. “The state governor… hates what we do here,” says Moira’s twin, “but what’s he gonna do? Send in his people to break down this tiny town? With the fucking wars going on?”

The wars, like so much else in Brother Brontë, remain unexplained. No matter. Flores’ book stands as a vivid account of how, even when catastrophe strikes, no experience is universal. A boot of oppression may constrict the throat of one community even as another nearby remains unimpeded, all while a “revolution without weapons” plays out further afield.

Volcanic ash pervades the sky, but within its eddies and swirls lies some possibility of redemption. With despair abounding outside my own window, I can’t help but take heart in Flores’ description of the smoke beginning to clear, his similes balanced between implicit violence and organic beauty. “A golden wink of sunshine pierced the sky like a bullet through cardboard,” he writes, “revealing a hint of something like dawn climbing her throne over Three Rivers.”

Earlier this month, I published a story for Columbia Journalism Review about the legal battle to force DOGE to abide by the Freedom of Information Act and other federal transparency laws. I’ll be staying on the press freedom beat as well as starting to get into some other reporting projects over the summer, but in the meantimes there’s been plenty happening on the publicity front for American Oasis. The Nation ran an excerpt from my chapter about the Sanctuary Movement on their website, and I also got nice write-ups from New Mexico Magazine and the website of my alma mater, Columbia University’s School of the Arts — as well as a frosty pan from the Wall Street Journal. Audio-wise, I had one lovely conversation with Will Rose from “Words on a Wire” on El Paso’s KTEP, and another with Cole and Bill Smead for “A Book with Legs.” Oh, and my two “Book TV” appearances on C-SPAN are now also online! Lastly, many thanks to Ray Delahanty for the nice shout-out of American Oasis on his delightful YouTube channel, CityNerd:

That’s all for now! Thanks, as always, for reading and subscribing. You can find me on my website, or marveling at all the jacaranda trees blooming under the May gray — that shade of purple can’t really be natural, can it?

Your pal,

Kyle