When Ugyen Wangchuk assumed his title as the first Buddhist monarch of Bhutan in 1907, a British diplomat named Jean Claude White was dispatched to the Himalayan kingdom from India as a representative of the subcontinent’s colonial government to its northern protectorate.

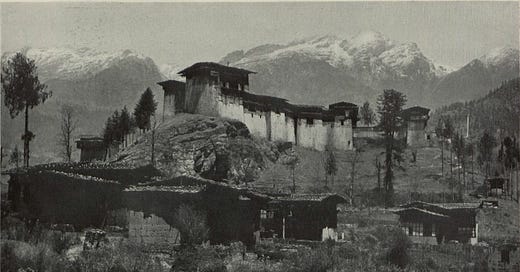

White had visited Bhutan twice before, and on each occasion had brought along a camera, stopping here and there to photograph tiny houses clinging to cliff faces and grand monasteries presiding over precipitous ravines. Seven years after his last visit, White’s photographs were published in a National Geographic feature titled “Castles in the Air,” along with an essay where White wrote that “it is impossible to find words to express adequately the wonderful beauty and varieties of scenery I met with during my journeys, the grandeur of the magnificent snow peaks, and the picturesqueness and charm of the many wonderful jongs, or forts, and other building I came across; but I hope my photographs may give my readers some idea of what I saw.”

After perusing “Castles in the Air,” an artist named Kathleen Worrell thought Bhutan’s distinctive architecture would be a perfect fit for El Paso. Worrell’s husband, Stephen, was the dean of the just-opened Texas School of Mines and Metallurgy, which was holding classes in the defunct El Paso Military Institute but hoping to build its own campus. In a letter to Robert Vinson, the president of the University of Texas, Stephen Worrell endorsed his wife’s idea, writing, “We have selected as a tentative plan a type of architecture suited to mountainous country, known as the Bhutanese.” When preliminary renderings were released in 1917, the El Paso Herald explained that the Bhutanese style was “characterized by ‘battered’ or sloping walls and flat roof, with wide overhanging cornices, and ornamental frieze” and that it would be “well suited to the site selected,” the hills hugging the Rio Grande just northwest of the city’s commercial district.

Whatever mystique the invocation of a far-off kingdom’s grandeur was meant to convey, the letter that Vinson wrote to the architect the university’s Building Committee had selected for the project, Henry Trost, made clear his hopes for the campus were not particularly romantic. “We should like to have a style of architecture adopted which will be as economical in the use of space as possible, with a minimum of exterior decoration,” Vinson wrote. “I have discussed the matter with Dean Worrell, and it is our desire to have a type of architecture which is peculiarly suited to the surroundings of El Paso, something along the order of the Mission type, or others which Dean Worrell will bring to your attention.”

This charge put Henry Trost in an odd position: on one hand, the city was primed for a grand spectacle, while the actual administrators footing the bill for the university’s new campus seemed inclined toward the functional. But Trost was nothing if not flexible. The architect had first found work in the 1880s and ‘90s as an ornamental metal designer in Chicago, at a time when Louis Sullivan’s early skyscrapers and the single-family homes of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Prairie School were creating a template for the modern American city. Trost designed his first house after moving to Tucson in 1899 and went on to nab commissions for a building at the University of Arizona and the local Carnegie Library. Four years later, he joined his younger brother Gustavus in El Paso and the two men went into business together, seeking to become the leading architects of the region stretching from Arizona to West Texas.

By 1917, Trost & Trost had designed dozens of buildings across what Henry liked to call “arid America,” adapting their style to the preferences of their clients. For the Mills Building on North Oregon Street in downtown El Paso, they created a lightly ornamented, Sullivan-esque skyscraper with an impressive, geometric façade that separated each bank of windows with a simple mullion, the pattern broken on the highest floor by an ornate balcony running the length of the block. Trost turned to the Mission Revival style for the Loretto Academy in Las Cruces, which featured an entry colonnade and a gently curving pediment. In Phoenix, his Water User’s Building on Van Buren and Second Avenue, where the federal Bureau of Reclamation kept an office, was meant to recall the Renaissance, with symmetrical rows of simplified Arcadian windows extending on either side of the column-framed front door.

Despite his knack for shapeshifting, Henry Trost struggled to find the right design language for the new School of Mines. His initial idea for the main building was rejected by Worrell, who complained, “They said in the beginning that they thought the Bhutanese was best suited to our location, but when they got through with it, it was not Bhutanese nor much of anything else, it was strictly Trost & Trost.” An engineering professor submitted some sketches in reply, which Trost dutifully incorporated into the final design. Now called Old Main, the building is a three story beige rectangle with walls that gently cant inward from bottom to top. Though the roof dramatically overhangs the walls, it is far from the sort of ornate pagoda that can be found in Bhutan; the best clue to the inspiration it took from a typical Dzong is the stripe of red that bands the top floor, with a tiled medallion between each window in the place where a golden mandala might otherwise hang.

The overall effect of Old Main is a curious, almost postmodern mashup: brickwork frames the entrance and forms an ornamental frieze over the stucco walls, all of it meant to emulate an imported style that appealed to one woman’s whimsy. In the logic of the Southwestern booster, this made the building a great success. Shortly after the first few buildings on the new campus opened in 1917, the El Paso Herald wrote, “With their soft-colored, dull walls, relieved with dull red brick work, ornamentation and roof, tile work reliefs and the touch of green under the overhanging roofs, the buildings show how well the architecture of the Bhutanese Indian type fits into the Texas desert country. The buildings look as if they grew there, and were indeed a part of the desert itself.”

As the School of Mines evolved first into Texas Western University and then into the University of Texas – El Paso, the Bhutanese motif became its signature. Today, practically every building on campus has an overhanging roof and a red band around its top floor. The Centennial Museum incorporates those elements into fieldstone walls and features decorative prayer wheels on either side of the main entrance; one of the latest additions to campus, the $80 million Advanced Manufacturing and Aerospace Center, features a two-tiered pagoda and a double layer of overhanging roofs. Starting in the 1980s, university officials began traveling to Bhutan to establish an actual connection with the country, and those efforts culminated in 2008, when UTEP became the permanent home of a Lhakhang, a small Buddhist temple that was built by Bhutanese craftsman and given to the United States as a gift. Inside are delicately carved columns and brilliantly painted frescos around a Choesham holding a seated Buddha and two other figures: Padmasambhava and Shabdrung Ngawang Namgyel.

That UTEP should have such a cohesive look yet be styled in a way that has nothing to do with its setting in the Chihuahuan Desert speaks to the colonial attitude that pervaded such projects around the turn of the 20th Century. When the third president of the University of New Mexico, William Tight, sought to create a similar, campus-wide design language in Albuquerque, residents were aghast that rather than import an architecture from elsewhere, he aimed to create “the pueblo on the mesa.”

After Tight engaged the services of Santa Fe’s John Gaw Meem, a popularizer of the Pueblo Revival style, anglo Albuquerqueans jeered his proposal to model a new central gathering place for students off the subterranean, circular kiva at the Kewa Pueblo, which could only be accessed by ladder through a hole in the ceiling. According to one critic, “If you are going to be consistent, the president and faculty should wear Indian blankets around their shoulders and feathered coverings on their heads.” For the boosters who hoped to Americanize the Southwest, it was more acceptable to insert the architecture of Bhutan into the arid foothills of the Franklin Mountains than it was to source a design for the sandhills of the Rio Grande from a community forty miles upstream.

This month’s Boston magazine includes my profile of Josh Kraft, the scion of the Patriots dynasty who seems to be gearing up to challenge Michelle Wu in the city’s mayoral election next year (at least, if the word on the street can be believed). Kraft is a fascinating guy — a longtime leader of the Boys and Girls Clubs of Boston, he’s got much deeper ties to the city’s working-class communities than you’d assume from his billion-dollar surname. Still, he faces a daunting opponent in Wu, who is perpetually underrated despite her enormous popularity and sterling electoral record. Take this piece as my little reminder that, for how overwhelming a national election like the one we’re staring down this fall can feel, it’s often through local politics where you can learn the most about the country’s evolving politics.

Last week I had my brain slightly rewired by watching How to Come Alive with Norman Mailer, Jeff Zimbalist’s striking new documentary about one of the 20th Century’s most popular authors, yet a figure who has seemed to fall out of the public consciousness far more quickly than peers like Philip Roth, J.D. Salinger, or Susan Sontag. Mailer’s acerbic presence as a public intellectual is the main motif of Zimbalist’s film, which doesn’t shy away from the most damning moments of his biography — namely when he nearly killed his wife by stabbing her in the heart during a fit of alcoholic rage — even as it positions Mailer as an oracular voice warning against how the compartmentalization and comforts of modern American life could pave the way for fascism. I left the screening somewhat unconvinced, as Mailer strikes me as a better reflection of his times than a barometer for our own. Nevertheless, it's an exquisitely assembled documentary and I found it refreshing to spend a few hours with a man whose undeniable brilliance and egotism did not drive him to avoid criticism and debate, but rather charge full-force toward it.

That’s all for now. Thanks, as always, for reading and subscribing. My website is currently offline as I make some, ahem, adjustments to prepare for the release of American Oasis: Finding the Future in the Cities of the Southwest. Speaking of, I hear that my publisher just got galleys in, so give a shout if you’d like to receive one to consider for a review, excerpt, or other publicity-related pursuit.

In the meantime you can find me on Instagram, or watching the DNC roll-call and wondering how Colorado of all places managed to bring more sauce to the party than my compadres in New Mexico.

Your pal,

Kyle